New York and the Fight for Community Alternatives

By the time Sharel Jones was in her late twenties, she’d been to Rikers Island more times than she could remember. Most often, like most women who are incarcerated in New York, she was sent to jail for possessing drugs or a crime she committed in pursuit of them, similar to most women who are incarcerated in New York. At that time in her life, Jones had been struggling with addiction for more than a decade so when she found out she was pregnant during intake at Rikers Island, she had mixed feelings.

“I was suffering from a lot of mental health issues. I was scared for the first time in my life,” Jones explained, “I was facing prison time. And it's like, what am I going to do with a kid? I'm not finished running the streets.”

Jones had already given birth to two children before her Rikers Island surprise, but she remembers little from those pregnancy and birthing experiences because of her drug addiction. Her other two boys were living with family members, and Jones said she never had to face the reality of being their mom full-time. Being incarcerated with this pregnancy meant Jones had little access to drugs and more of an obligation to parent, and that was terrifying.

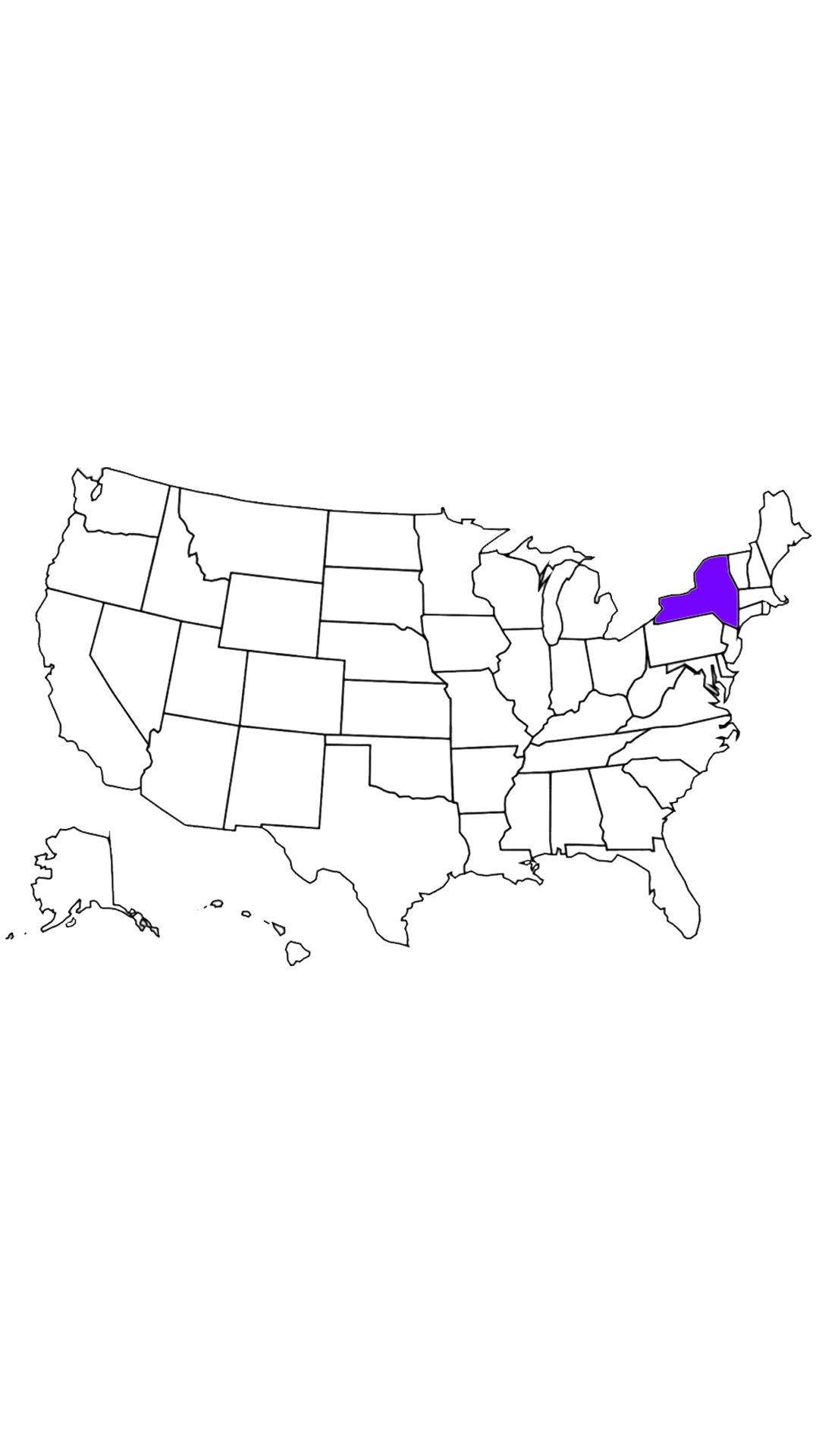

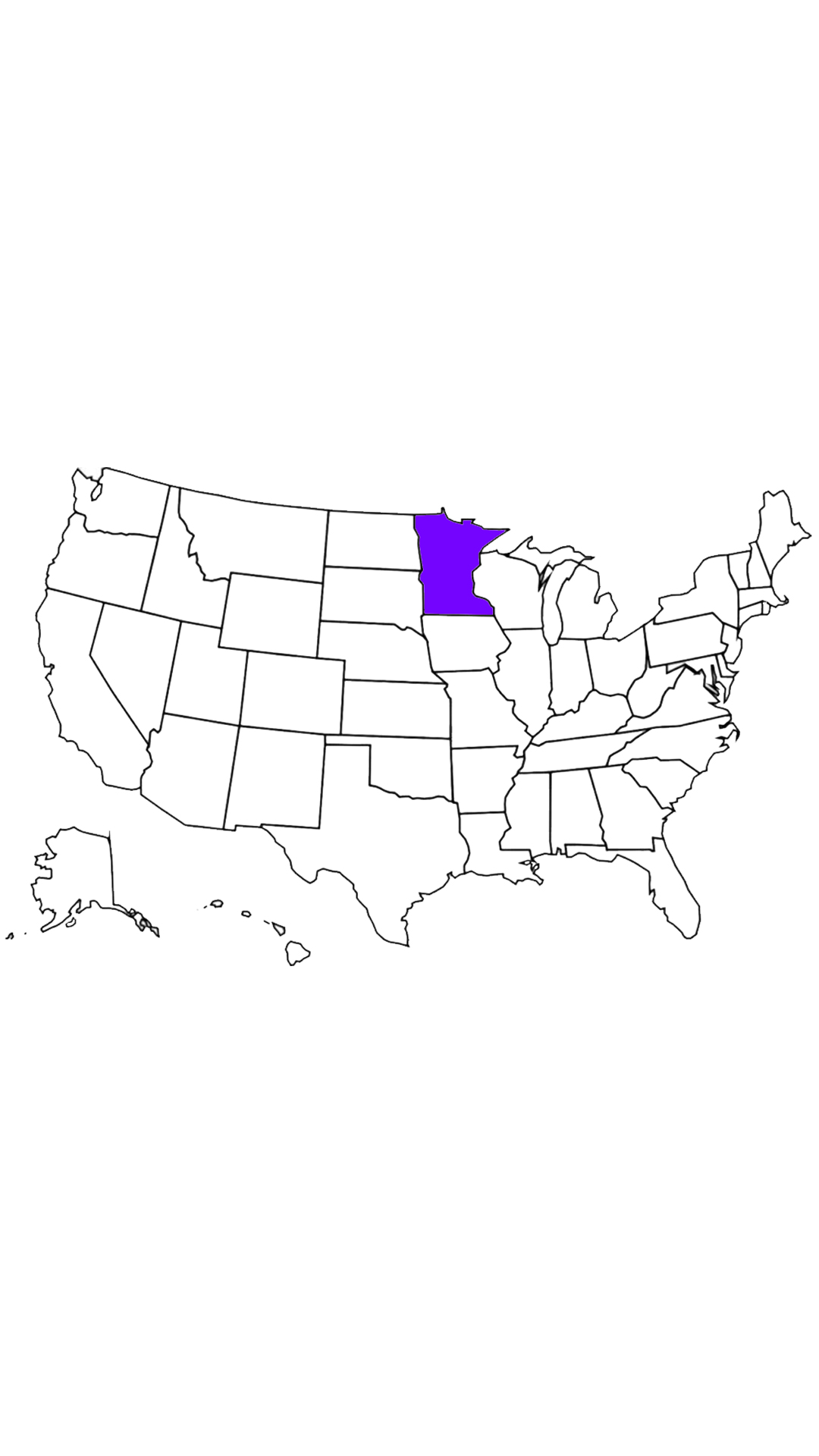

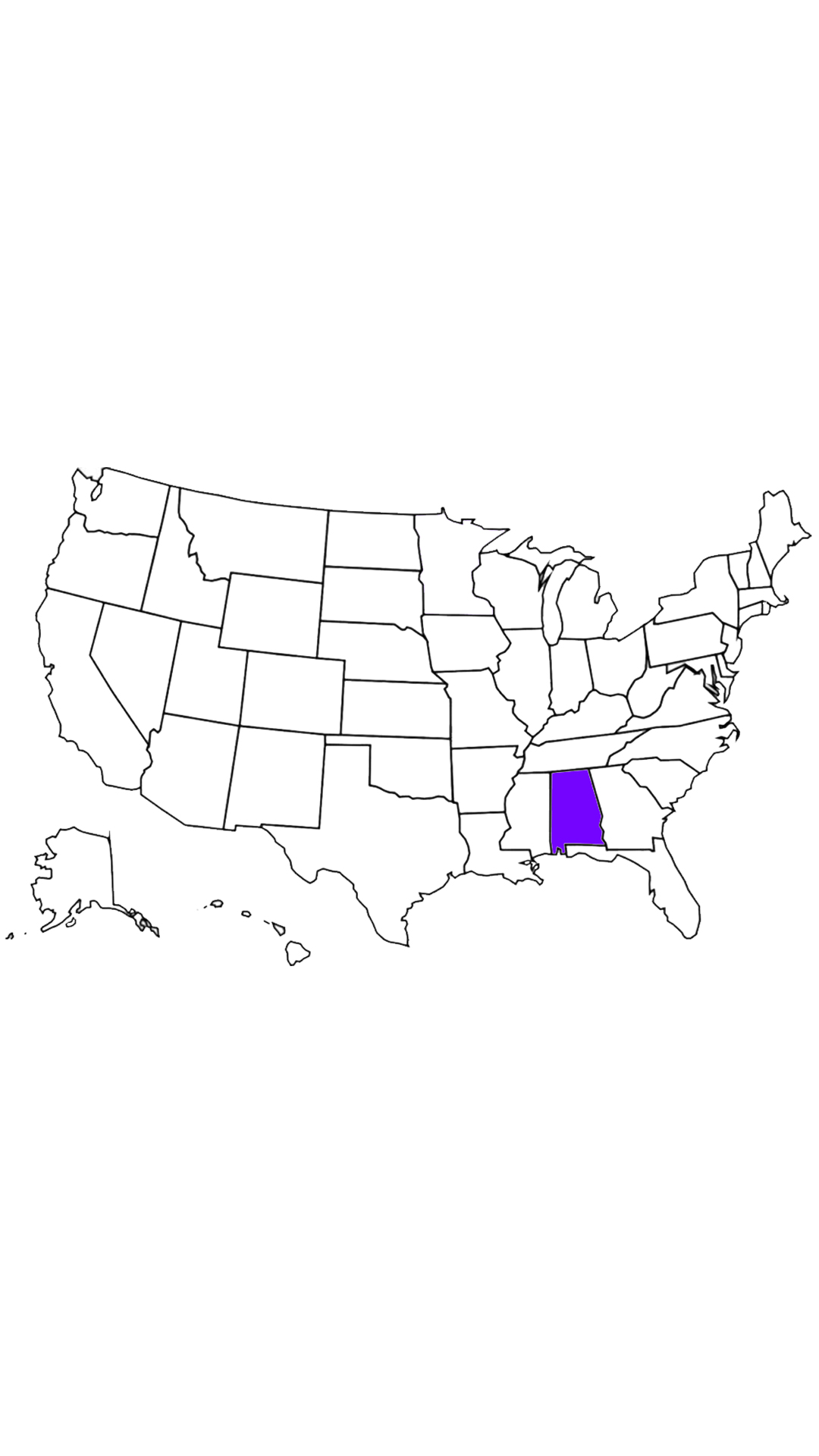

New York is one of only eight states in the country that allows pregnant people to keep their children for up to a year after giving birth in a special nursery program. When Jones learned she was 13 weeks pregnant, she was placed in a separate facility at the Rose M. Singer center women’s jail on Rikers, one that had other pregnant people, pastel colored walls and all the baby gear she’d need. Jones also got to participate in a lullaby program with Carnegie Hall where she wrote and recorded a song for her newborn.

“You wouldn't know that that's a part of the jail, the nursery,” Jones said, “It’s very different. It’s just like outside.”

On Thanksgiving day in 2012, Jones’ son Ariyon was born. Jones chose her son’s birthday, opting for a cesarean section at the advice of her doctor which is not an uncommon suggestion for prison births. She decided giving birth would be the most joyous way to spend the holiday.

“They later on brought me my son and I'm like, Oh my God. It's about to get real,” Jones recalls, “I had never changed Pampers. I had never did the milk thing with my kids. I didn't have to do those things.”

Ariyon was able to live with his mom inside Rikers Island for the first four months of his life. His older brothers sometimes tease him about the fact that he was born in jail, but Jones says he brushes it off. She never hid her struggles with her kids and likes that they can now talk freely about such complicated memories.

Jones was later sentenced to 1.5-3 years following the birth of Ariyon and was sent upstate to Bedford Hills Women’s Prison where there’s also a nursery program, but it was difficult for Jones to be accepted to it because of the nature of her crime. Though she was able to gain access to the program through some advocacy from family members, Jones was quickly disenrolled because she got into a fight with another woman.

The situation Jones faced when she was sent upstate to Bedford Hills is not unfamiliar to many people who give birth while incarcerated. It’s part of the reason why Dr. Lorie Goshin, Associate Professor at Hunter College’s Bellevue School of Nursing who studies pregnant people in New York’s carceral system, is questioning benefits of having a nursery program if entry is limited to non-violent offenders, people who don’t have a history of child welfare involvement and sometimes people on psychotropic medications.

“When you take a group of women and you pull out all the women who fit any of those criteria, you don't have a lot of people left, because if you fit that criteria, you shouldn't be in prison anyway. It's often that there aren't a lot of women that these programs would serve,” Dr. Goshin said.

Even so, Dr. Goshin thinks pregnant people shouldn’t go to jail or prison at all. Instead, she’d rather see them placed in incarceration alternatives like residential treatment programs or supportive housing. One of Dr. Goshin’s studies looked at the long-term effects of babies kept in prison nursery programs with their moms, comparing their developmental outcomes to those of children who were separated from their mothers due to incarceration. She and the other researchers found that the babies kept with their mothers did have some better mental health outcomes. But that study didn’t account for another possibility.

“We did not compare those kids to kids who had been able to stay with their moms in a supportive community setting. So something like supportive housing where the mom got the support that she needed for, for example, history of trauma, or substance use disorder, or homelessness or whatever created her pathway to incarceration,” Dr. Goshin explained. “We were unable to compare that experience, which I believe would be a better approach to pregnant people who are involved in the criminal legal system.”

I feel like no one is going to raise my child like I would.

When Sharon White-Harrigan was serving a 10-year prison sentence for manslaughter at Bedford Hills, she was already a mom to a young daughter. White-Harrigan did not give birth to her child while incarcerated, but being in prison nonetheless had a detrimental effect on her daughter. White-Harrigan says she struggled with arranging care for her child from miles away upstate and wrestled with the thought of her visiting, not wanting her child to deal with the hassle and emotional toll of seeing her mom in prison.

“It was tough when you have children, I feel like no one is going to raise my child like I would,” said White-Harrigan. “And during the years, it just was really, just really difficult.”

When White-Harrigan was in Bedford Hills, she unintentionally started her activism from the inside, making her way through different positions on the Inmate Liaison Committee which acts as a middleman between the prison population and the administration. White-Harrigan served as secretary treasurer, vice president and eventually president where she pushed for things like washer and dryer accessibility and beauty tools for when the women had special events or court dates.

“I just went into action. It wasn’t anything that anyone taught me. I just felt like people deserved to have [things],” White-Harrigan said.

After her release, White-Harrigan has continued her advocacy for women involved with the carceral system, now serving as executive director of the Women’s Community Justice Association where her main goal is similar to that of Dr. Goshin’s: for women to not go to jail or prison at all, instead fighting for community alternatives.

Poster from a rally coordinated by the Women's Community of Justice Association and organization, “Communities Not Cages”

“One of our recommendations is to divert pregnant women. So that means that they wouldn't go to Rikers or any other kind of secured facility in that way that there will be a place where they can be nurtured, where children could be nurtured,” White-Harrigan said. “We understand that pregnant women commit crimes and get in trouble. But we also think that the children, the unborn children should not be subjected to any kind of harm, or in any way be a part of that process.”

In her vision, White-Harrigan imagines residential treatment programs or supportive housing that treats the problem rather than punishes the person. In this alternative reality, White-Harrigan says families wouldn’t be separated, which is a vital option for the over 80% of women who are parents and oftentimes primary caregivers for their children and families.

“I've heard people in the community say, Well, you know, if she was worried about the kid, you wouldn't commit a crime. Right? And so, you know, some people don't feel like there should be any specialized treatment for people because they don't know how to separate the act from the person,” White-Harrigan explained.

Models like these already exist in New York, Dr. Goshin said, like one managed by the Women’s Community Justice Project, which bears a similar name to the WCJA White-Harrigan heads but is different in that it provides housing and treatment alternatives. But, as Dr. Goshin explains, enough resources aren’t being put into them as a viable solution.

“Their early outcomes have been excellent in that they've been able to keep women safe in the community, some of whom were pregnant, and their more recent work is providing supportive housing to women and their children. So either coming directly in with kids if the person has current custody, or allowing the mom to reunify,” Dr. Goshin said. “But it's a relatively small program. And certainly receives a lot less resources and support, than Rikers Island and just locking women up.”

There is some hope for advocates of these community alternatives, though. In October of this year, Governor Hochul and Mayor De Blasio announced that the Rose M. Singer women’s jail on Rikers Island would be shut down. At the time of the announcement, just 230 women were incarcerated there. That’s a stark difference from the over 6,000 men who were also on the island. The women were transferred to Bedford Hills and another facility upstate. But that isn’t exactly the solution some people were hoping for.

“We need help, not jail,” Jones said. “What we have to start doing is in our homes and in our communities finding other ways because the pain stems from something. We don't just wake up and say, Hey, today, I'm going to smoke crack. Today, I just want to try heroin. We're trying to numb something, we don't want to think about something. And I think if we get more community centers, if we get more women on health services, it'll be much better.”

Jones has since been in recovery from her addiction for six years. She doesn’t live with her children, but still maintains a relationship with them. She says her time on Rikers Island didn’t do much to help her address her traumas, treat her addiction or restore that relationship with her children. Jones said that took the work of her will and support on the outside.

Sharel Jones and her children, Malik, Naziah, and Ariyon (from left to right), provided by Sharel Jones

White-Harrigan has also struggled with her relationship with her daughter. Now an adult, her daughter spent most of her life not in her mom’s care. When White-Harrigan thinks back to her time at Bedford Hills, she says the most meaningful support she received was from fellow incarcerated women, most of whom were also mothers, dealing with similar strifes as she. It’s what drives her continued advocacy work on the outside.

“We have a real sisterhood, a real camaraderie. The good, the bad, the ugly, the right, the wrong, the indifferent,” said White-Harrigan. “I think that there's this unspoken connection with all of us. Whether we know each other, or you came behind me, or you left before me, there's this unspoken connection that you know, we're sisters.”